Though the the coronavirus has ground the nation to a halt, business continues, if at a slower pace than it did in the Before Time.

This includes the NCAA's name, image and likeness efforts. In a video chat with CBS News legal analyst and NCAA correspondent Jack Ford, Division I vice president Kevin Lennon provided an update on the organization's talks, announced back in October, have accomplished nearly six months in.

And from the start it slaps you in the face that the NCAA is still, well, the NCAA. It's the same people, the same verbiage, the same approach. The only difference this time is the NCAA is pretending liberalizing the organization's archaic name, image and likeness rules are their own idea, not forced at proverbial gunpoint by laws passed in numerous statehouses across the country plus parallel federal efforts in Washington.

"We're really beginning from a point of change as we look at the 21st century student-athlete," Lennon said. "I think some of the things that I have heard from the group are that, while we need to modernize -- and I think you will see robust proposals to do that -- there's been a real commitment and re-focus on the value of the collegiate model and making sure that whatever is done does not reflect a pay-for-play model, does not create an employee-employer relationship. So while the advancement is moving forward, what I've seen is a real commitment to the true value of the collegiate model and making sure that whatever we do to enhance the name, image and likeness opportunities for student-athletes, it's done within the context of the collegiate model."

To be clear, no one is talking about a "pay-for-play" model, where athletes would receive paychecks from their schools, though the issue has been purposefully conflated with the NIL model by the people in power over the years in order to preserve the status quo.

The only serious models under discussion in statehouses across the land and in Congress are those that allow college athletes to trade their status for payments from third-parties. Lennon said the goals of the committee are to preserve the "collegiate model," to resist an "employee-employer relationship" between athlete and school, and to "protect the integrity of the recruiting process."

After months of committee discussion, Lennon said the NCAA will soon begin mailing out materials for consumption and soliciting feedback, and that the process will begin its "public" phase where the broader membership can weigh in later this month, starting with a meeting on April 24.

"I think there are some that are (going to be) surprised, candidly, at how far these recommendations are going," said Lennon. "I think people will be very impressed by the thoughtful nature in terms of how we're going to go about helping our young people. As we continue to expose the membership, getting greater expertise from their insights, that at some point in time we'll be ready to take legislative action when it's appropriate."

Of course, the NCAA lost control of this issue a long time ago. College athletics leadership can talk all the want about paradigm shifts they feel comfortable with, but there are laws on the books in multiple states, with more coming. It's quite possible that legislators at both the state and federal levels could look a the NCAA's "robust" proposals (Lennon used that word three times, by my count), shrug, and continue about their business of burning the system down to the studs.

In the meantime, Athletic Director U released a study that found, based on industry rates, the highest-profile college athletes could earn real money through social media alone.

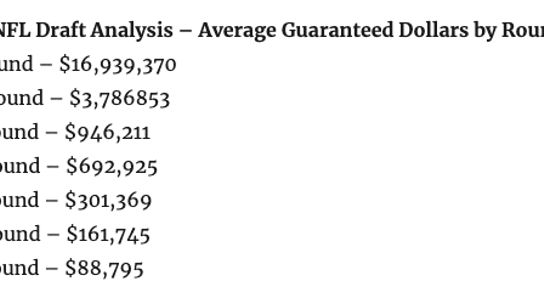

While it would undoubtedly be a shock to the system for a star quarterback to compare bank accounts with his offensive coordinator, there's a chance this could turn into a net positive for college football. Ninety-nine players left school early for the 2020 NFL Draft (a slight dip from the 103 of 2019). Some of them will go in the first round, but most won't. Some won't even be drafted. NFL contracts are non-guaranteed and each year dozens of players forfeit their college eligibility for the chance at, say, a $400,000 signing bonus.

If a junior defensive back can turn his Instagram following into, say, $50,000 in guaranteed money through endorsements, perhaps he's more likely to stick around, play his senior season, work on his craft, improve his draft stock and, as a byproduct, earn his degree in the process. The smart schools have realized an open NIL market can benefit them and their players and have already started making preparations for the coming shift. We'll soon find out if college ADs and presidents can think as far ahead as their football recruiting departments.