As in most sports, college football head coaching hires seem to operate on a pendulum. After firing a head coach, the decision makers often pinpoint the problem with the current head coach and then run in the opposite direction, convinced that will fix the program's problems. A defensive-minded coach is replaced with an offensive mastermind. An old coach is replaced by a young coach. A taskmaster is replaced with a player's coach, unless the team is too soft, and then a taskmaster is brought in to whip the boys into shape.

And when college football programs fire a black head coach, they almost always replace him with a white coach.

Texas did it, turning Charlie Strong to Tom Herman. Texas A&M did the same, exchanging Kevin Sumlin for Jimbo Fisher. Wind the calendar back a few years and you'll find Mississippi State replacing Sylvester Croom with Dan Mullen, and Notre Dame replacing Tyrone Willingham with Charlie Weis.

On and on it goes. In fact, in a FootballScoop analysis reaching back to 2000, only one school (East Carolina) has fired a black coach (Ruffin McNeill) and replaced him with another black coach (Scottie Montgomery).

This trend is not well-known among the general public, but is clearly seen in black coaching circles.

"What I push for and what I think all other black coaches push for is (a coach) to be evaluated on their own merits," Willingham told FootballScoop. "And that would be the same for a black coach, a white coach, a Hispanic coach or anybody that's coaching. That should mean that an African-American coach can follow an African-American coach, a white coach can follow a black coach, but the door and the opportunity for good coaches should be available, and that seems to be where we're lacking. That door is not opened for good coaches. One group is being totally dismissed. That should not be the case."

At present, 13 of the 130 (10 percent) FBS programs employ black head coaches. That's more than double the six black head coaches in 2008 and the five in 1998, but down from the 16 in 2012. It's also below the share of black population in the United States at large (13.4 percent, according to the Census Bureau) and well below the number of black football players in major college football, which the NCAA lists at just shy of 50 percent.

There are a number of reasons for this. Unlike the NFL, where 19 percent of the league's 32 head coaches are black (not including the recently-dismissed Hue Jackson), there is no nation-wide Rooney Rule to mandate at least one minority candidate interview for head coaching jobs. And unlike the NFL, where only one or two signatures are required to hire a head coach, there are many more cooks in the kitchen in the college football -- from the university president and board of regents to the athletics director and major donors. The need to please so many constituencies leads to a more conservative decision-making process

"The head football coach at a Division I school is the face of the university," a former FBS head coach told FootballScoop. "There are very, very, very few African-American presidents and very, very few African-American athletic directors. That's who's doing the hiring. The face of the university, for most of the people that are on the board, some of them have an issue with that."

Another contributing factor: there aren't as many black coaches in position to get head coaching jobs as their white counterparts.

A FootballScoop analysis of all 130 FBS coaching staffs found the following:

- 31 FBS schools employ black defensive coordinators. Of those 31, 11 carry co-coordinator titles.

- 19 FBS schools employ black offensive coordinators. Of those 19, seven carry co-coordinator titles and 16 coach a position other than quarterbacks.

- In fact, only four FBS schools employ black quarterbacks coaches. Of those four, two (Joe Dailey of Liberty and Ivin Jasper of Navy) are also offensive coordinators. (Alabama offensive coordinator Mike Locksley does not handle a specific position.)

- Nine FBS schools employ black offensive line coaches. One of those nine is listed as an assistant offensive line coach.

When zoomed out to a 30,000-foot level, it's easy to send a trend -- very, very few black coaches are permitted to coach the more "cerebral" positions.

"There's a perception that anybody can coach running backs, anybody can coach receivers, anybody can coach DBs," a Power 5 assistant coach told FootballScoop, who was granted anonymity to speak freely without fear of retribution. "That's a position where athleticism will trump ability in coaching. That's the perception. That's wrong, but that's the way it is."

"Just like they used to say that black quarterbacks couldn't think," the former head coach said.

Again, this is where the political process of FBS coaching hiring plays a factor. If black assistant coaches are hired to coach and recruit running backs, wide receivers and defensive backs -- positions that are almost exclusively black at the FBS level -- it can make it tough to also hire a black coordinator, specifically on offense, without tipping off the racial balance of the staff.

"There's a certain dynamic on the staff, and coaches are really, really sensitive to that. 'I've got to make sure I've got the right mix on my staff.' There's boosters looking, there's people looking," the Power 5 assistant said. "They want to know."

"You might have African-Americans on the staff, but a lot of them are hired just to recruit," said the former FBS head coach. "They want them to recruit, relate to the kids, talk to Momma and be able to relate to them."

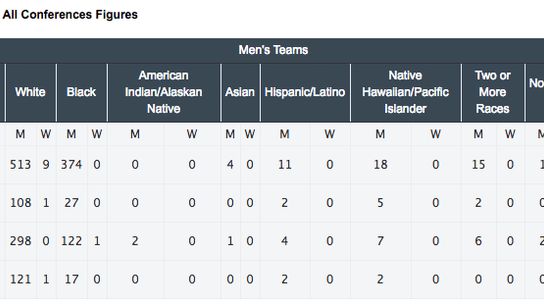

At the bottom of the totem pole, the numbers of black graduate assistants lag behind white graduate assistants. According to NCAA statistics, nearly 64 percent of FBS GAs are white, while just over a quarter are black.

Put all the puzzle pieces together and you'll find a system so vast that no one person controls it and, thus, one that no one person can change it. It's a living, breathing organism that reinforces the survival of the status quo, subsisting on college football's it's-who-you-know culture.

"With nepotism in the coaching ranks, because you have so many Caucasian coaches, I think when there are GA positions opening up you just have white people hiring white people," said Bryan Blair, a coaches' agent with Sports Consulting Northwest. "I don't think it's on purpose, I think it's just human nature."

Some believe a Rooney Rule could work in college football. Others aren't so optimistic.

"It would be a farce. They'd find ways around it," the former head coach said. "They'd bring a guy in off their staff and say, 'I interviewed a guy. I gave him serious consideration. I even promoted him and named him assistant head coach.'"

Another prong to the issue is the collapse of the Black Coaches Association. Though the BCA had no hiring and firing power, it was an effective megaphone for its constituents, providing needed accountability to the issue. No similar organization has risen up to fill that void.

"(Coaches, ADs and administrators) didn't have to answer to the BCA, but they knew the BCA was listening and taking notes," the FBS assistant said. "It had a voice and it had an audience."

"I think when it was strong and when it had the financial backing, I think we made a difference," former BCA executive director Floyd Keith said. "The statistics and data were hard to argue. We had a voice and an advocate. I never had a problem with putting the knowledge out there because a lot of it is people being aware of what the issues might be. The whole issue has been accountability. You've got to have an instrument to whole the process accountable that is fair and equitable and diverse. Without that, you're kind of like a street corner vendor, you're just trying to holler and you hope people will listen. You couldn't debate the stats. The stats were obvious."

By and large, black coaches feel they're further along than they were 20 years ago, but not as far along as they should be. Numerous coaches pointed to James Franklin at Penn State and David Shaw at Stanford as important representatives in high-visibility positions that can propel more administrators to hire black coaches and more young black men to get into coaching. Franklin in particular was mentioned unprompted in nearly every interview I conducted in reporting this story.

"There's got to be enough of a visibility of a success rate for people to look at it and say, 'Well, that's a route I want to go.' You have to see some progress," Keith said. "You have to be able to look and see, 'That choice is something that I want to do.'"

Most of all, black coaches want to be treated like white coaches -- not as representatives of their race, but as individuals who are hired and fired on their own merits. For example, here was Kevin Sumlin's answer at his introductory press conference at Arizona this past January when asked about being the school's first black head coach:

“This is my third time being a head coach and I’ve been asked that every time. The goal is that that question is not only asked but not the first question that comes out.”

As far as this issue, the culture and the nation as a whole has come, black coaches feel there's still work to be done to reform a system they don't control.

"Black coaches have done seminars, they've done conferences, they've done everything they can do," Willingham said. "They've gone to the same schools, the same churches, they've done everything you can do to position themselves to be in those windows of opportunities. Why the reason they're not hired, I don't know. I think if we were told what the reasons were, then we would work and improve those areas to be able to do that."

"When we get jobs, we've got to win and we've got to win the right way. Like James Franklin, wins at Vanderbilt and gets the Penn State job," the FBS assistant said. "When you win, people will come after you."